Translation in all Senses

‘But through the endless afternoon

These neither speak nor movement make.

But stare into their deepening trance

As if their grace would never break.’

Edwin Muir

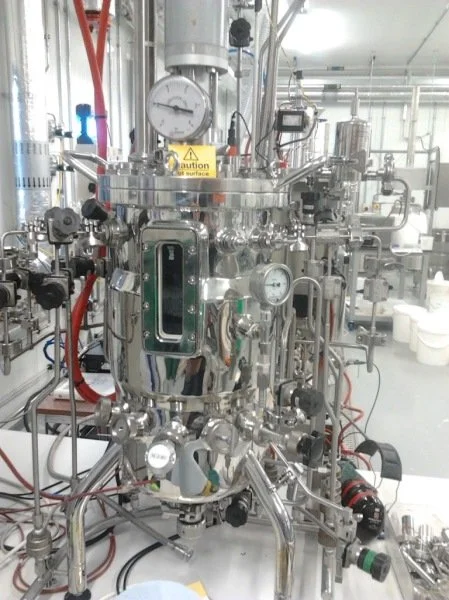

Metaphor: the most fascinating element of language. This photograph of the beautiful silver machine to be found in one of the laboratories at Goggerddan, Aberystwyth is set to transform food science and how and what we eat. Seeing it for the first time a few weeks ago, its intricacies of tubes and wires reminded me of how both science and language abound in metaphors to perceive and describe abstract concepts, and as human culture becomes more and more complex so new means of expression assert themselves. Take flora; its Latin indicants as well common English names such as, Queen Anne’s Lace , buttercup, ladies-slipper , all concrete metaphors that express our powers of perception about the world around us and our understanding of it. The etymologies of words like the convolutions of the seed machine pictured above and which in turn contain a type of ‘divine knowledge’ : It resembles, I think, a nervous system, out of which imaginative possibilities are realised.

. . . all good poets, epic as well as lyric, composed their beautiful poems not by art, but because they are inspired and possessed . . . there is no invention in him until he has been inspired and is out of his senses and the mind is no longer in him.’ So said Plato in Io and his sentiments were answered by Shelley in his A Defense of Poetry:

‘A man cannot say, “I will compose poetry.” The greatest poet even cannot say it; for the mind in creation is as a fading coal, which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness . . . and the conscious por- tions of our natures are prophetic either of its approach or its departure.’

The poet, unravels thought, the scientist DNA . The impulse and being come from each other. The verb ‘to be’ comes from the Sanskrit bhu, ‘to grow or to make grow’ while the English forms ‘am‘ and ‘is’ have evolved from the Sanskrit ‘asmi‘ to breathe. What a lovely thought that the most commonplace of our verbs are records of the time when humans had no independent word for ‘existence’ and could only utter that something ‘grows’ or ‘breathes’. Whilst we may not be conscious that ‘being’ is generated from a metaphor about breathing and growing, new conjunctions bring about new kinds of relatedness and new kinds of emergents.

‘ The one note all the leaves make as rain runs over them,

The leaf-note that winds into the deep sough of the trunk

That unwinds along all the root-tapers, down into the atoms… branching canopies

Of lights and ethers’

Peter Redgrove from Four Tall Tales

conserving ancient pathways in red and blue

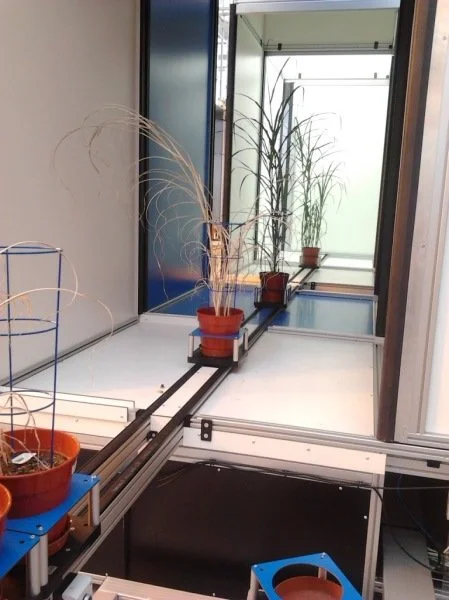

Gardeners are absent from the greenhouses at Goggerddan, Aberystwyth. Instead plants are tended in a different way, moving along a conveyor belt and given nutrients and water at specific intervals. Every so often plants are photographed and the details recorded. When a plant becomes hot, for example, it closes its pores to prevent water from escaping: such details are detected by infrared cameras. This is Phenomics: the study of an organism’s physical and biomechanical characteristics.

The human genome project brought a surge of experimentation and allowed scientists to uncover the DNA of every living thing. Such science will change lives by helping to feed the extra millions of people likely to populate the planet in the coming decades,as well as encouraging plants to deal with the extreme weather climate change will bring.

Understanding the string of ‘letters’ is a complicated business and how the various genetic sequences connect to heritable traits, and discovering and understanding how these genotypes affect attributes such as drought tolerance and speed of growth has been much slower in progress. This crop breeding is not genetic modification but a means of removing the trial and error processes of earlier times when looking at a group of plants and measuring a single plant leaf in an experiment could take up to two days. Now, the ‘imaging cabins’ provide accurate measurements and much more besides, such as calculating the amount of water a plant may take in over a period of time, its temperature and its ability to photosynthesise. These plants will be our food and may also become fuel for cars. The plants are uniquely identified and are individually watered and fed.The plants are observed to detect minute changes in their processes and the adaptations are noted. Our food at present is subject to being encouraged to grow by the use of synthetic fertilisers: expensive to produce and the reserves of key nutrients such as phosphorus is beginning to deplete. The work at Goggerddan intends to identify the genes that will help the plants to adapt to climatic conditions by being hardier and more productive. There is a quiet revolution going on in these greenhouses in Wales.

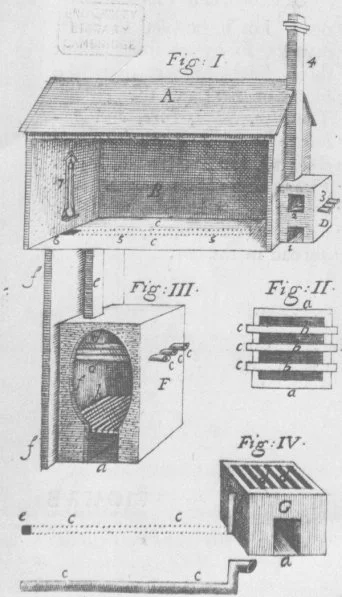

John Evelyn’s Greene-house 1664.

Evelyn is credited with the introduction of the word ‘conserve ‘to mean Green-house, short for Conservatory. He is also credited with introducing the word Greene-house in 1664. The two words gradually came to have different meanings

Evelyn spoke of the ‘excellent Botanist Mr Ray, who said, ‘The Use of Plants is all our Life long of that universal Importance and Concern, that we can neither live nor subsist in any Plenty with Decency or Conveniency or be said to live indeed at all without them…’